How Aviation Began in its Earliest Forms

Beginnings

12 September 2020

If you ask an American who figured out how to fly, they’d probably say the Wright brothers. Although they were the first to create a powered airplane, their achievements were on the backs of millennia of scientists and tinkerers.

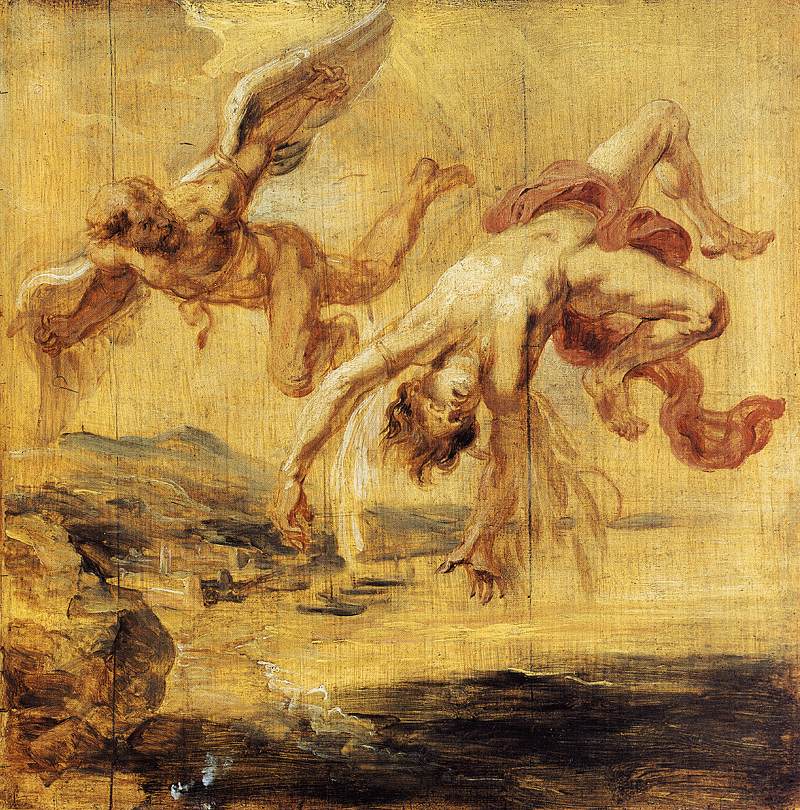

The Fall of Icarus

Peter Paul Rubens, 1636

Depiction of Ahura Mazda in Iran. Image via Encyclopedia Britannica, from the University of Chicago Oriental Institute

Let’s take a look at ancient China first. They didn’t get any people up in the air, but they did create some interesting flying machines. Take the kite, for example. It is believed to have been invented in China during the 5th century BC. Used to aid in military communication, it was initially made from bamboo and silk, but then paper when it was invented during the Han dynasty. As the cost of kites decreased, its use became more widespread and to this day remains a beautiful form of Chinese arts and crafts.

Consider also the sky lantern, the earliest form of a hot air balloon. It too was invented in China and uses a small flame in the bottom of what is essentially a large paper bag. This was also used for military communication. Like the kite, the use of the lantern has transformed, and people now appreciate the lantern as a symbol of hope and wonder.

A sky lantern festival in Taiwan

Image by Yunjie Liao, via Al Jazeera

Mikhail Zarezin's drawing of Ibn Firnas and his glider

During the Islamic Golden Age were the first recorded attempts of human flight. A man named Armen Firman used a large cloak to jump off of a tower in Cordoba in the year 852. The cloak acted like a glider/parachute which slowed him down enough that he survived with only minor injuries.

A young man named Abbas ibn Firnas watched Firman make his tower jump and was inspired to build his own glider. In 875, Firnas made a mostly successful flight, except for the landing in which he hurt his back. Today, a statue of him rests outside of Baghdad International Airport in Iraq.

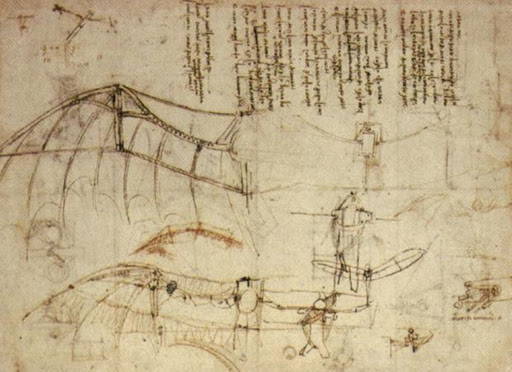

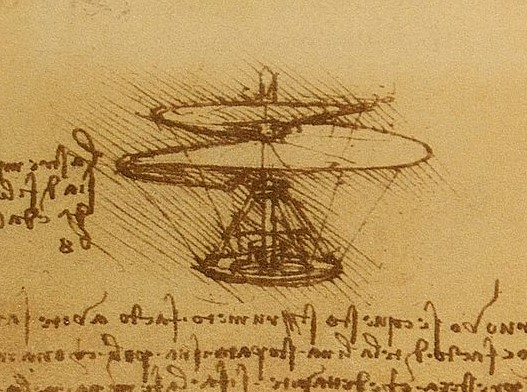

During the renaissance, European inventors took a stab at flying. Notably, Leonardo da Vinci was obsessed with the idea of a human powered flying machine. Da Vinci made detailed studies and attempts at a human powered ornithopter and a new invention called the Aerial Screw. Modern scientists agree that his machines would not be physically feasible for multiple reasons, but his detailed studies and experiments represent a systematic, scientific approach to human flight.

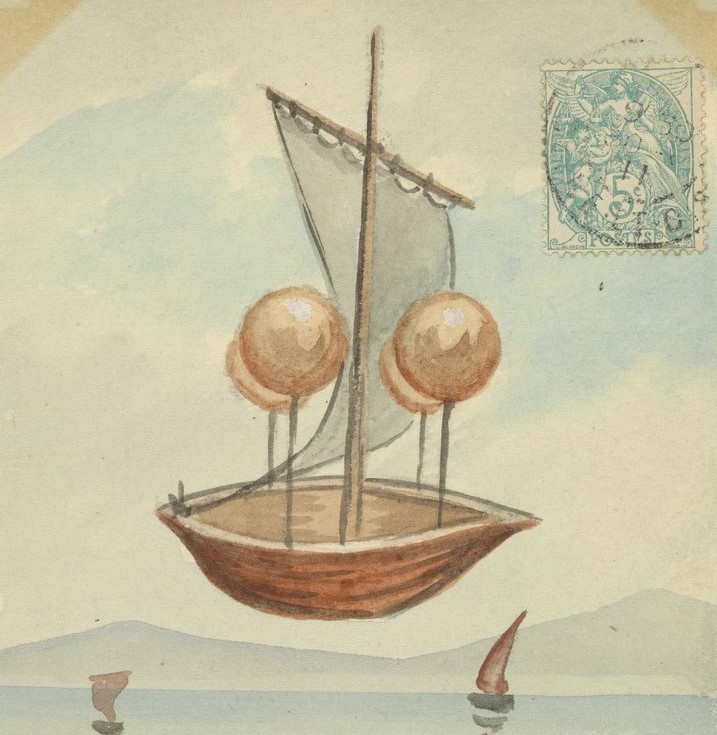

Another renaissance man, Francesco Lana de Terzi, was inspired by mathematicians and physicists of his time in the 17th century. Rather than birds, de Terzi was inspired by boats. Indeed, he designed a flying boat that used vacuumed air from copper spheres to rise off the ground.

Da Vinci's flying machines: (1) human powered ornithopter (2) Aerial Screw

Part of a 1909 postcard drawn by A. Molynk, commemorating de Terzi's flying airship

His design was never built and scientists agree that it couldn't have, given the technology available to him. However, his work paved the way for the development of future lighter-than-air aircraft like balloons.

For many of the achievements mentioned above, one might question whether they should be considered "aviation". Although something like a sky lantern might not seem to have anything to do with an airplane, the observations and questioning that stemmed from these inventions helped people to better understand how air works, and imagine how they might go about designing something that could fly.

References

- "An Air Balloon Invented in the Last Century." Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum, March 1, 1789. https://airandspace.si.edu/collection-objects/an-air-balloon-invented-in-the-last-century/nasm_A20140515000.

- Deng, Yinke., Wang, Pingxing. Ancient Chinese Inventions. United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press, 2011.

- The Editors of Encylopedia Britannica. "Ahura Mazdā." In Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, inc., November 25, 2015. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Ahura-Mazda.

- Goodheart, Benjamin. "Tracing the History of the Ornithopter: Past, Present, and Future." Journal of Aviation/Aerospace Education & Research, 2011. https://doi.org/10.15394/jaaer.2011.1344.

- Jamsari, Ezad Azraai, Mohd Aliff Mohd Nawi, Adibah Sulaiman, Roziah Sidik, Zanizam Zaidi, and M. Z. A. H. Ashari. "Ibn Firnas and his contribution to the aviation technology of the world." Advances in Natural and Applied Sciences 7, no. 1 (2013): 74-78.

- Jue, David. Chinese Kites: How to Make and Fly Them. United Kingdom: Tuttle Publishing, 2012.

- Lienhard, John H. "No. 1910: Abbas Ibn Firnas." The Engines of Our Ingenuity. The University of Houston College of Engineering, 2003. https://www.uh.edu/engines/epi1910.htm.

- MacDonnell, Joseph. "Francesco Lana-Terzi, S.J. (1631 - 1687) The Father of Aeronautics." Fairfield University. Department of Mathematics. http://www.faculty.fairfield.edu/jmac/sj/scientists/lana.htm.

- Peabody, Josephine P. "Icarus and Daedalus." Essay. In Old Greek Folk Stories Told Anew, edited by Judith V Lechner, 36–39. London: George Harrap, 1910.

- Petrescu, Florian Ion, and Relly Victoria Petrescu. In The Aviation History, 5–7. Norderstedt: Books on Demand, 2012.

- Scholz, Matthias P. "The Aerial Screw." Advanced NXT, 2007, 227–75. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4302-0258-5_6.

- Wonning, Paul R. A Short History of Kites: History of Flying – The Kites Role in Aviation and the Airplane. N.p.: Mossy Feet Books, (n.d.).