The spark that killed an entire mode of transportation

Safety

23 May 2021

May 6, 1937. Lakehurst, New Jersey. 7 o'clock PM. German Zeppelin LZ-129 Hindenburg is nearing the end of its three-day long luxurious transatlantic journey from Frankfurt. The passengers on the Hindenburg are looking out the window of the giant airship, experiencing a bird's eye view of the ground, a privilege reserved for only the world's wealthiest. Little did they know, many of them would die in an instant.

The airship was beginning to make its final descent after a few hours of circling, as the weather was rather poor and the crew was waiting for the rain to stop. Although it wasn't currently raining, the crew was eager to land the airship before the weather could get worse. During the descent, the airship began taking on a nose-high attitude, which the crew responded to by dropping bags of water ballast, weights that assist in maintaining the trim of the aircraft. When that was unsuccessful, six crewmembers were told to go to the bow to keep the ship in trim, which worked.

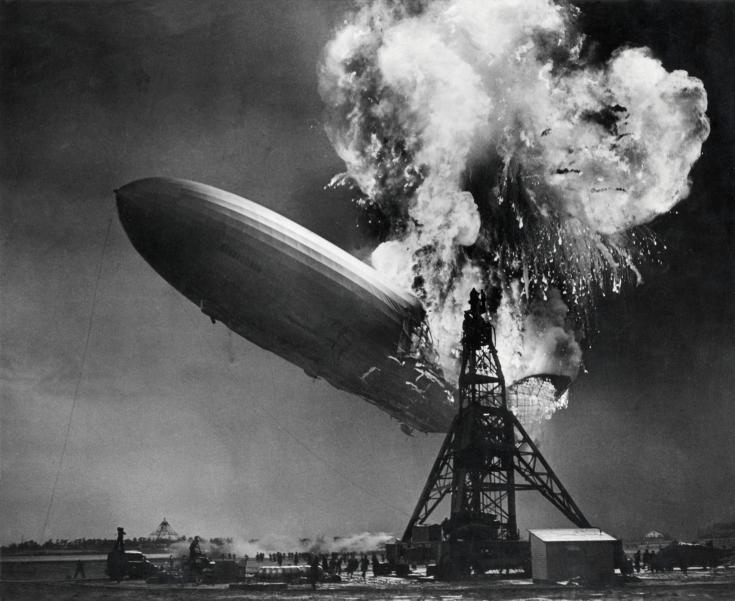

The Hindenburg as it first ignites in a large explosion. Photo by Sam Shere; public domain.

The ship continued its descent, with ground crews now in place to assist. The mooring lines are then dropped from the airship; less than 30 seconds later, a loud explosion is heard. Flames engulf first the rear of the ship, then quickly spread towards the front, the ship plummeting to the ground. The skin of the airship burns first, revealing the aluminum alloy frame, which falls to the ground and collapses; it was completely consumed in just thirty-four seconds. A huge column of black smoke rises from the site of the crash for several hours as the remains of the airship burn and are put out by fire crews. Of the 97 passengers and crew, 35 died.

Though highly publicized and with footage available of the disaster, the exact cause of the crash is still an incomplete picture. However, there are many theories of why it happened.

One such theory involves the greater historical picture of the time - Nazi Germany was operating these Zeppelins, and there was quite a bit of political tension. In fact, Zeppelins were never intended to be filled with hydrogen gas - helium was supposed to be used, but Germany couldn't get its hands on any since the US controlled most of the product and its trade. For a long time after the accident, most believed that it was the doing of saboteurs who wanted to make a statement towards Nazi Germany. However, these theories have been largely discredited, and there was not much substantial evidence to justify them.

Passengers look out the small windows of the Hindenburg's cabin. Photo via the Spaarnestad Collection; public domain.

The next theory: electric charge. Because it had been raining before the Hindenburg attempted to land, and the weather was poor enough to make the crew want to land before it started raining again, the clouds were an issue. Lightning itself is a result of a charge accumulation due to clouds rubbing against each other, much like how charge accumulates when you walk across carpet or rub a balloon in someone's hair. When the potential difference between the ground and sky is greater than the breakdown voltage of air, lightning strikes. In the case of the Hindenburg, even before it ignited, a phenomenon known as St. Elmo's Fire was observed. This occurs when a charged object discharges through air (similar to lightning), but because of differences in charge distribution due to the geometry of the object (pointed areas typically have a greater voltage). Because this was seen on the Hindenburg, it shows that the airship was indeed electrically charged. As the airship exploded soon after the mooring lines were dropped, we can infer that the electrical grounding of the ship via the ropes caused a spark, which ignited the hydrogen sacs and caused the airship to burn.

In 1997, former NASA scientist Addison Bain proposed a new theory, known as the Incendiary Paint Theory. He claimed that the fabric used to cover the airship was covered in flammable paint, which was the primary cause of the ignition. Bain said that the paint contained iron oxide and aluminum, which are the reagents in the thermite reaction. There are several pieces of evidence to support this theory. For one, the airship remains somewhat level as it burns, which might suggest that the hydrogen sacs were still intact. Second, the color of the flame was yellow, which isn't characteristic of hydrogen. Finally, Bain got his hands on some of the original fabric used in the construction of the Hindenburg and conducted his own burn test, which showed that the fabric burned similarly to how the airship burned in the disaster.

However, the true story is likely a mixture of the two theories, as there are also several pieces of evidence that discredit the Incendiary Paint Theory. In the video, the airship appears to have burned from the inside out, which is expected if the hydrogen burned first. Second, the airship had been struck by lightning before, which burned holes in the fabric but didn't ignite the entire ship. Finally, static discharge doesn't produce enough heat to ignite a thermite mixture, if that's what made the paint flammable.

There was likely a leak in one of the hydrogen sacs, which would not have been unlikely. The St. Elmo's Fire observed before didn't ignite the hydrogen since it didn't occur near the site of the leak, but a spark near the leakage could easily cause an explosion, which is probably what happened. The paint did burn though - the color of the flame and the fabric burn test did not lie, but it was the extreme heat of the burning hydrogen that caused the fabric to ignite secondarily. The airship stayed level because of the upward convective current from the hot air, much like how hot air balloons themselves work.

As the Hindenburg went up in flames, so did the rest of the airship industry. The disaster brought the abrupt end of this form of travel, for reasons easily understood. But, why was the Hindenburg the one to do it? Before it, there had been several airships that had gone up in flames, crashed, or hit obstacles. Perhaps it was the magnificence of this incident, or that World War II was quickly approaching. In any case, airships were no less a symbol of innovation, luxury, and a part of history to be remembered.

Primary source footage from British Pathé, a popular newsreel producer at the time.

References

- Graham, Tim. Hindenburg: Formula for Disaster. ChemMatters, 2007 12. https://www.acs.org/content/dam/acsorg/education/resources/highschool/chemmatters/articlesbytopic/biographyandhistory/chemmatters-dec2007-hindenburg.pdf.

- Grossman, Dan. "The Hindenburg disaster". Airships.net. https://www.airships.net/hindenburg/disaster/.

- "Hindenburg". Encyclopaedia Britannica, 2019. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Hindenburg.

- "Scenes from Hell: Herb Morrison - Hindenburg Disaster, 1937". United States National Archives. https://www.archives.gov/exhibits/eyewitness/html.php?section=5.

- Webster, Donovan. "What Really Felled the Hindenburg?" Smithsonian Magazine, 2017. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smithsonian-institution/80th-anniversary-hindenburg-disaster-mysteries-remain-180963107/.